About the Author

Mehri Madarshahi; Advisory Committee Member of the International Centre for Creativity and Sustainable Development under the auspices of UNESCO; and Honorary Professor of The Institute of Public Policy (IPP), South China University of Technology (SCUT).

Introduction

The physical risks of a changing climate were underlined in recent months when the world's most powerful tropical cyclone of 2025 hit the Philippines twice in a few days in November 2025. Typhoon Kalmaegi made landfall across central Philippines causing flash flooding and landslides particularly in the province of Cebu, where entire communities were washed away with a heavy death toll. It then moved towards Vietnam.

Just days after Kalmaegi, Fung-Wong hit the Philippines with sustained winds of 185 km/h and gusts of up to 230 km/h displacing 1.4 million people displace/evacuated. This display of back-to-back major storms within days reveals the acute stress on urban and regional resilience systems.

Shortly before, Typhoon Ragasa struck southern China. A rapid-attribution study by the Grantham Institute found that climate change made Ragasa about 49% more likely, with roughly 36% of the damage in southern China attributed to anthropogenic warming. Its winds were boosted by approximately 7% and rainfall by 12% due to warming.

In July this year, the Pakistan Monsoon Floods, killed more than 300 people, submerged over 4,000 villages, and damaged extensive infrastructure including major roads and bridges along the Indus River.

According to the Report on Climate Change and the Escalation of Global Extreme Heat (May 2025), four billion people, 49 percent of the global population, experienced at least 30 days of extreme heat during the study period. In 195 countries and territories, climate change has at least doubled the number of extreme-heat days. This pervasive heat stress carries major implications for urban health, building design, infrastructure resilience, and the planning of green spaces.

The same study, referring to State of Wildfires 2024–2025 (Copernicus ESSD), notes that in northeast Amazonia, extreme fire-weather conditions during January to March 2024 were 30 to 70 times more likely due to anthropogenic climate forcing, a pattern also observed in the Congo Basin. These tropical forest fire events severely affected biodiversity, ecosystem services, and carbon storage, and they also influenced nearby urban regions through degraded air quality, population displacement, and disruptions to watershed systems.

Equally alarming was the extreme rainfall in Spain's Valencia region during autumn 2024, where a single day's precipitation equaled the annual average. The resulting flash floods caused widespread destruction of homes and significant loss of life.

This dramatic series of extreme weather events in recent months has captured global attention and raised pressing questions about the accelerating impacts of climate change. As the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) warns, "Many of these changes are unprecedented, and some of the shifts are already in motion, while others, such as continued sea-level rise, are 'irreversible' for centuries to millennia." The Panel further cautions that unless "rapid and deep reductions in CO₂ and other greenhouse-gas emissions" occur soon, the goals of the 2015 Paris Agreement will slip beyond reach.

Yet as the world grows hotter and catastrophic events increase, governments that once championed climate action with strong political backing appear increasingly disengaged from today's challenges.

UN Framework Convention on Climate Change - COP 30

On 12 November 2025, world leaders gathered in Belém, the capital of Brazil's Pará state, for the 30th Conference of the Parties (COP 30) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), reaffirming that nature conservation is now firmly embedded in the COP agenda.

A major geopolitical shift, however, was evident. Leaders from China, Russia, Australia, Indonesia, Turkey, and Japan were absent. Most strikingly, the United States, participating at the highest levels for three decades, sent no senior officials. For the first time since the global climate process began, the world's largest historical emitter was effectively missing from the table.

Under the Trump presidency, the United States has withdrawn from key commitments to curb fossil-fuel use, both domestically and internationally. It has undermined global efforts by blocking an international limit on petroleum-based plastics production and preventing adoption of the world's first tax on shipping emissions. This policy U-turn stands in stark contrast to the remarkable climate advances of the private sector, which now confront growing headwinds from political uncertainty, fiscal constraints, and geopolitical fragmentation.

Despite these obstacles, the climate economy continues to expand. Since 2015, the global market for green technologies, including solar photovoltaics, wind turbines, electric vehicles, and batteries, has nearly quadrupled, surpassing $700 billion annually and demonstrating the sector's commercial viability. Members of the World Economic Forum's Alliance of CEO Climate Leaders, representing more than $4 trillion in revenues, collectively reduced emissions by 12 percent while increasing revenues by 20 percent between 2019 and 2023. Yet this progress remains vulnerable without coherent government policy.

The Significance of Brazil as Host

By hosting COP 30 in Belém, gateway to the Amazon rainforest, which contains roughly 60 percent of the world's largest tropical forest, Brazil sends an unmistakable message: nature is central, not peripheral, to climate stability.

This is the first COP ever convened in the Amazon Basin, a region that represents both one of the planet's greatest carbon sinks and one of its most fragile ecosystems. The symbolism is profound. The Amazon functions simultaneously as a sanctuary of biodiversity and a barometer of global ecological health. Holding COP 30 here underscores the deep interdependence between environmental conservation, human security, and climate governance.

The Amazonian setting offers a powerful metaphor for resilience one that extends beyond forests to the design of sustainable, climate-adaptive cities. As the United Nations emphasizes, COP 30 represents a critical juncture for assessing whether the mechanisms of the Paris Agreement are delivering tangible results. "COP 30 must ignite a decade of acceleration and delivery." The stakes are indeed formidable.

Brazil's own urban experiments, from flood-management reforms in São Paulo to sustainable mobility initiatives in Curitiba, illustrate how national commitments can drive innovative action at the municipal level. By situating global climate negotiations in the heart of the world's largest tropical forest, COP 30 reinforces the essential continuity between ecological and urban resilience, a continuity fundamental to achieving a just and sustainable global transition.

Despite the momentum generated by the Paris Agreement (2015), global emissions remain on a trajectory that risks surpassing the 1.5 °C threshold. The 2023 Global Stock revealed that the commitments submitted by Parties, Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), would, if fully implemented, still result in an estimated 2.5–2.9 °C of warming by the end of the century. The conference in Belém therefore represents a pivotal opportunity not only to strengthen ambition but also to operationalize existing commitments through implementation, finance, and accountability mechanisms.

Nationally Determined Contributions

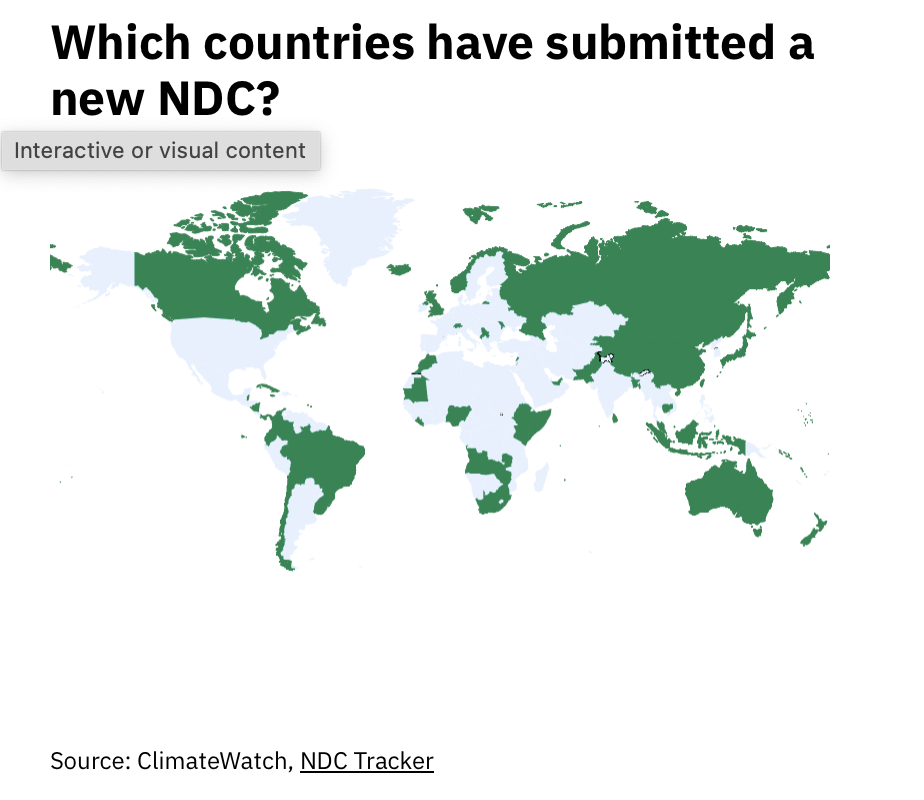

By 2025, countries were required to submit their third generation of Nationally Determined Contributions " NDCs 3.0' representing their most ambitious climate

pledges yet. These updated NDCs, covering the 2025-2035 period, must have demonstrated significant progression aligning with the 1.5°C temperature goal. But progress has been sluggish. According to the Climate Watch NDC Tracker, with China submitting on 3 November, only 69 major economies, representing 61% of greenhouse gas emissions (GHG), have submitted these plans. This amounts to a reduction of emissions of 10%. We would need 60% of the global community to stay within 1.5°C to meet the requirement of the Paris agreement. This sluggish response is even though the global market for green technologies, including solar photovoltaics, wind turbines, electric vehicles, and batteries (as mentioned above), has nearly quadrupled since 2015 to exceed $700 billion annually, a testament to the commercial viability of the climate economy.

Expectations and Challenges for COP 30

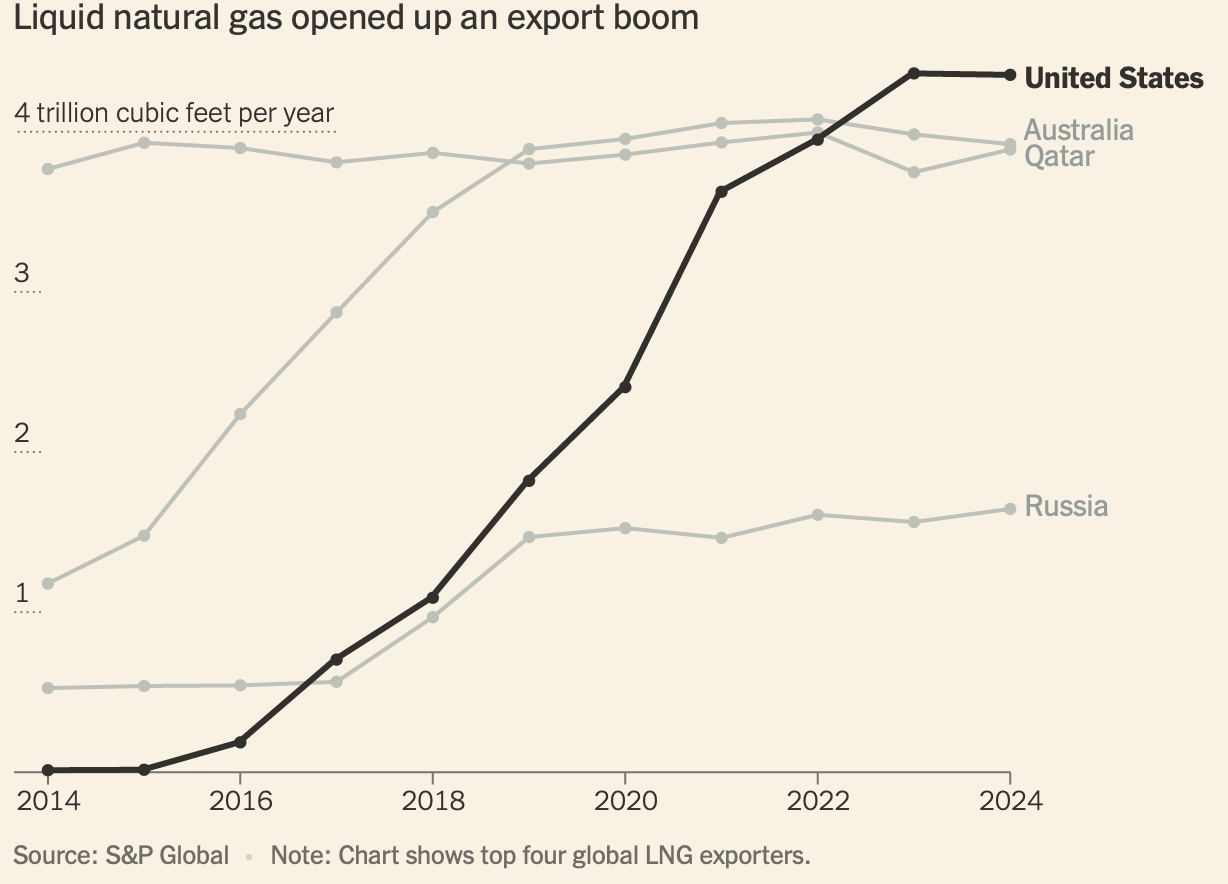

Three decades after the first COP in Berlin, the climate regime has evolved from a diplomatic negotiation forum into a complex system of multi-actor governance. COP 30 crystallizes this transformation. Over the decade since the Paris Agreement was signed, the United States rapidly become the world's leading producer and exporter of gas.

The Trump administration not only abandoned America's promises to the rest of the world that it would control the greenhouse gas, but as the opposition leader, is pressuring other countries to similarly back away from efforts to fight climate change.

Meanwhile, China is doubling down on its effort to become the world's preeminent "electro state"—a leading producer of green technologies and a global climate leader..

China installed more wind turbines and solar panels last year than the rest of the world combined. It now dominates clean energy industries, from patented technologies to essential raw materials, and is selling a lot of it to the world. Chinese companies are building electric vehicle and battery factories in Brazil, Thailand, Morocco and Hungary.

The Global South, long peripheral in decision-making, is now asserting itself through more active participation as a co-author of the climate agenda, assert themselves as a co-author of the climate agenda. The conference also reveals an evolving architecture of climate governance. Power and initiative are no longer concentrated solely in traditional Western actors but increasingly shared among emerging economies, subnational governments, and transnational city networks. Brazil's leadership reflects this shift, positioning the Global South not as a passive recipient of climate policy but as a co-author of its future. The growing prominence of cities, regions, and Indigenous coalitions within the COP process also illustrates a decentralization of agency a move toward a more polycentric form of global environmental governance. Brazil's leadership embodies this shift, seeking to reconcile developmental imperatives with ecological stewardship.

The symbolic power of convening COP 30 in the Amazon extends beyond forest preservation: it also invites reflection on how the principles of ecological balance, adaptation, and justice can be applied to urban environments. Cities, home to more than half of humanity and responsible for over 70 percent of greenhouse-gas emissions are increasingly recognized as critical frontlines of climate action. The discussions in Belém thus have profound implications for urban policy, infrastructure planning, and climate governance.

COP 30 is widely regarded as a test of the Paris Agreement's credibility and of the world's collective political will. Beyond technical negotiations, it embodies a contest of trust — between North and South, state and citizen, human development and ecological limits. Central expectations revolve around three domains.

First, the ambition gap. Parties are expected to submit updated NDCs aligned with the 1.5 °C pathway before 2026. The success of COP 30 will depend on whether major economies, including emerging ones, demonstrate measurable progress in phasing out fossil fuels and scaling up renewable systems.

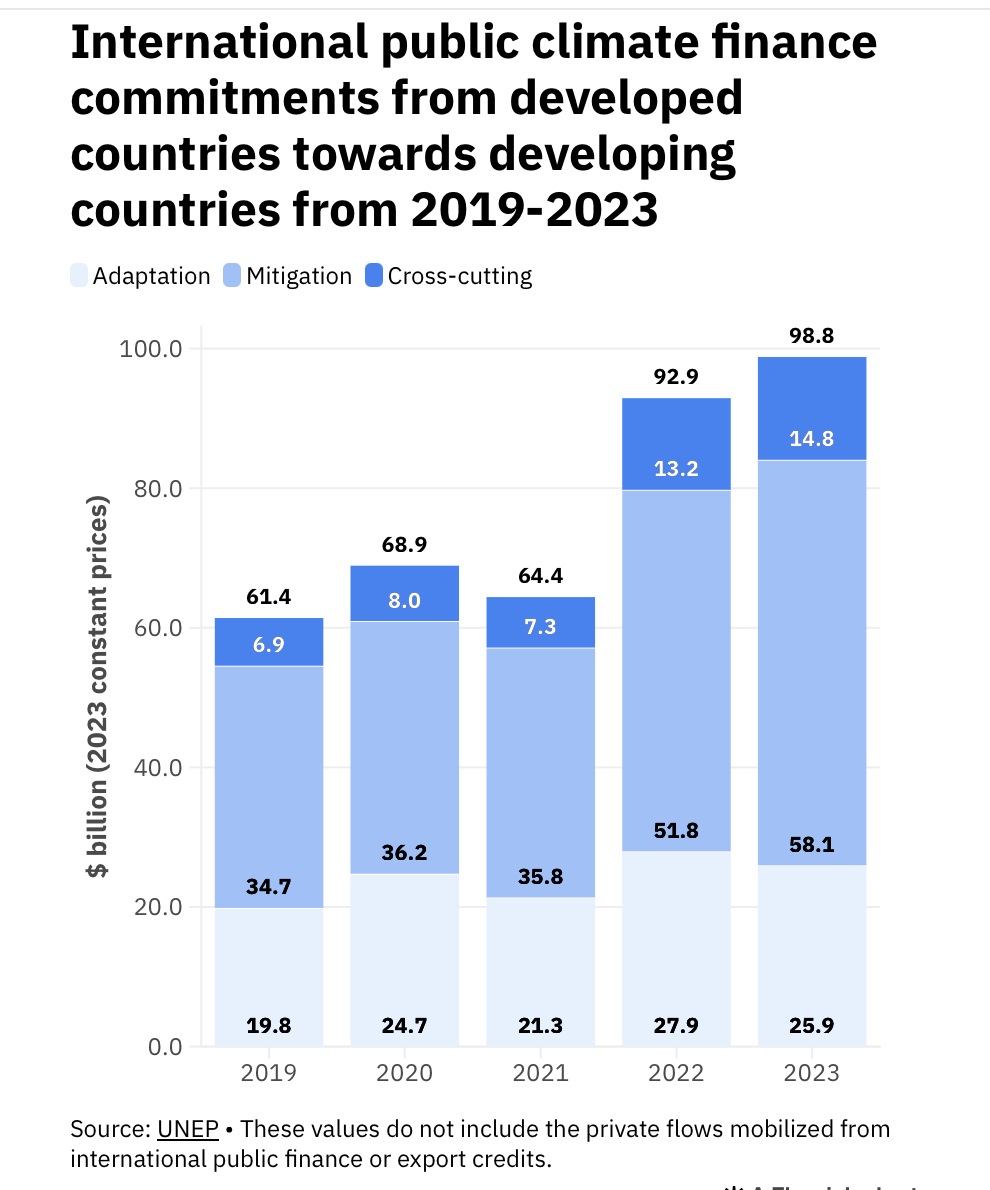

Second, climate finance. Brazil, as host, seeks to expand commitments beyond the long-standing USD 100 billion annual pledge and to establish instruments that grant developing nations and subnational entities direct access to funds. This is especially crucial for adaptation, a dimension historically underfinanced relative to mitigation. One of the key tenets of the Paris Agreement was an acknowledgement that countries had different responsibilities. Wealthy industrialized countries were supposed to support poorer countries on transition to renewable energy and adapt to the problems brought on by a hotter climate.

Last year, countries agreed that a total of $1.3 trillion would be needed every year by 2035 to help developing countries manage climate harms, including $300 billion a year in public monies from rich countries. That's far more than what rich countries have so far made available. Where that money will come from is still uncertain.

Expectations concerning climate finance, long recognized as the cornerstone of implementation. Brazil has signaled that, "The world must be moving on, even without U.S. political and technological leadership, "and emphasizes its intention to push for expanded commitments beyond the long-standing USD 100 billion annual pledge and to establish mechanisms that facilitate direct access to finance for developing nations and local governments. The tension between mitigation and adaptation financing remains acute: while large-scale renewable transitions attract investment, funding for resilience, nature-based solutions, and loss-and-damage remains severely under-resourced.

Third, governance and equity. The conference will confront widening divergences between developed and developing countries over carbon markets, loss-and-damage mechanisms, and accountability frameworks. It will also test the capacity of multilateralism to accommodate plural forms of leadership and innovation, from national governments to cities, regions, and Indigenous coalitions.

In this light, the outcomes of COP 30 could redefine how global commitments cascade into municipal action. Enhanced financing for adaptation, clearer metrics for nature-based solutions, and recognition of ecosystem services can directly influence local climate strategies. The principle of resilient cities integrating green infrastructure, social inclusion, and adaptive design mirrors the Amazonian ethic of coexistence between human and natural systems. Brazilian experiences such as flood management in São Paulo, urban reforestation in Curitiba, and participatory housing in Recife exemplify how national frameworks can foster city-level experimentation.

Thus, the "Amazon lens" of COP 30 underscores the continuity between ecological and urban resilience. It invites a paradigm shift in which sustainability is no longer framed as a trade-off between development and environment, but as an integrated approach to planetary and civic well-being.

COP 30 will test multilateral governance itself. Divergences between developed and developing countries over equity, carbon markets, and accountability mechanisms have widened since COP 28 in Dubai. As the summit unfolds in the Global South, it faces the dual challenge of mediating these divides while maintaining credibility as a science-based, equitable forum for collective action.

Ultimately, COP 30's true significance will be measured by its potential to bridge divides: between mitigation and adaptation, between ecology and economy, and between global vision and local reality and less by the scale of its declarations. Its success depends on whether the international community can transform moral urgency into institutional redesign, embedding resilience, equity, and scientific integrity at the heart of global decision-making. In this sense, COP 30 is more than another milestone; it is a test of humanity's capacity to realign its developmental trajectory with the ecological boundaries of the Earth.

The Amazonian setting of COP 30 transforms this paradox into a moral and political test, a reminder that the effectiveness of the multilateral system should be judged not by the elegance of its declarations, but by the tangibility of its outcomes.

In this sense, COP 30 is not merely another conference; it is a litmus test for the credibility of the international climate regime and a measure of humanity's capacity to realign its development paradigm with the limits of the planet.

A subsequent article will analyze the achievements.